▴ Cluster of images in the Old City in occupied East Jerusalem

Surveillance stifles activism

Hebron

Palestinian human rights defender Issa Amro was taking some fellow activists on a tour of Hebron on 11 June 2022, when they encountered an Israeli soldier. Initially civil, the soldier turned hostile when he scanned Amro’s face with an app on his smartphone.

“Before 2021, facial recognition technology was only at checkpoints but since 2022 it’s in the hands of every soldier in their mobile phones. The soldier scans our faces with the phone camera, and suddenly their behaviour towards us changes, because they see all the information,”

Amro was arrested, bound in plastic handcuffs and taken to an abandoned house where the soldier threatened to kill him.

A few months later, on 31 October 2022, Israeli soldiers raided the offices of Amro’s organization, Youth Against Settlements, and declared it a closed military zone. The closure was reinforced by cameras on the nearby military base and Israeli settlement, also located on Shuhada Street, now directed at the offices…. in a serious violation of the activist group’s rights to freedom of association, expression and peaceful assembly.

Amro said being subjected to constant remote surveillance was “dehumanizing”.

“We don’t know how soldiers are using this information, and we don’t know what they have access to or what they will use against me. There is no influence we can have on the system. We don’t vote for who uses it. We can’t go to court to change some kind of regulation. It doesn’t take into consideration our culture, our need for privacy.”

▴ Pan, tilt and zoom (PTZ) cameras looking out over East Jerusalem

East Jerusalem

Mass surveillance cameras and other AI-driven technologies are steadily transforming the landscape across East Jerusalem. They give Israeli security forces an insidious means of policing protests, monitoring places of particular social, cultural or religious significance to Palestinians, such as the Al-Aqsa mosque, and keeping track of areas targeted for expansion or takeover by settlers.

Located in East Jerusalem, the Damascus Gate is mostly used by Palestinians to enter Jerusalem’s Old City. has long been a gathering point for Palestinians to reclaim a sense of community and express themselves through protests, including in support of prisoners on hunger strike or against Israeli offensives on the Gaza Strip. Protests are routinely suppressed by Israeli undercover agents and security forces using arbitrary force, including chasing protesters with horses, firing stun grenades and administering severe beatings.

The Damascus Gate and surrounding areas are under constant surveillance. This has only increased since July 2017 when protests erupted over metal detectors that were installed by Israeli authorities at the Al-Aqsa mosque compound following the killing of two Israeli security officers. This resulted in Palestinian worshippers refusing to enter Al-Aqsa through the metal detectors. Instead, they congregated outside in an act of civil disobedience.

Persistent popular pressure forced Israel to remove the metal detectors. But they were replaced with smart cameras on 25 July 2017, a move opposed by many Palestinians. One protester told Amnesty International: “Cameras for us played exactly the same role as the metal detectors, although less visible. We realized that their aim was to control us.”

Only when both the metal detectors and the newly installed cameras were removed did Palestinians end their protest on 27 July 2017. Recognizing the role that the Damascus Gate played as a springboard for protests, Israel was keen to tighten its control of the space, gradually but steadily increasing the number of surveillance cameras and militarizing the area.

▴ Damascus Gate in East Jerusalem

Old City, New Tech

From the predominantly Palestinian neighbourhood of Sheikh Jarrah to the Damascus Gate, a distance of about two kilometres, the Israeli authorities have installed blanket camera surveillance as well as surveillance towers equipped with cameras and sensors. While the infrastructure is most visible at Damascus Gate, it is pervasive throughout East Jerusalem, particularly inside the Old City, where new surveillance technologies collide with old patterns of harassment, dispossession, segregation and denial of rights.

The Israeli surveillance system of choice in the Old City is Mabat 2000. It was installed at the turn of the millennium with the aim of mounting CCTV cameras in as many streets and alleyways as possible. In 2017, Israeli authorities began upgrading the system to support facial and object recognition, watch listing (tracking persons of interest) and predictive tools to identify and locate Palestinians on a police ‘watchlist’. Since then the Mabat 2000 programme has only expanded.

In 2020, the Jerusalem municipality was reported to have deployed 1,000 cameras, as well as video analysis technology to “identify unusual activity in public areas in order to manage public space and transportation”. It said some of the cameras were capable of carrying out object recognition, and that 100 cameras were “connected to servers that then can analyse data”.

In March 2022, Who Profits described how 400 CCTV cameras placed across the Old City were broadcasting live-feeds of residents’ movements to the police 24 hours a day in an operation run by a central police Command and Control centre.

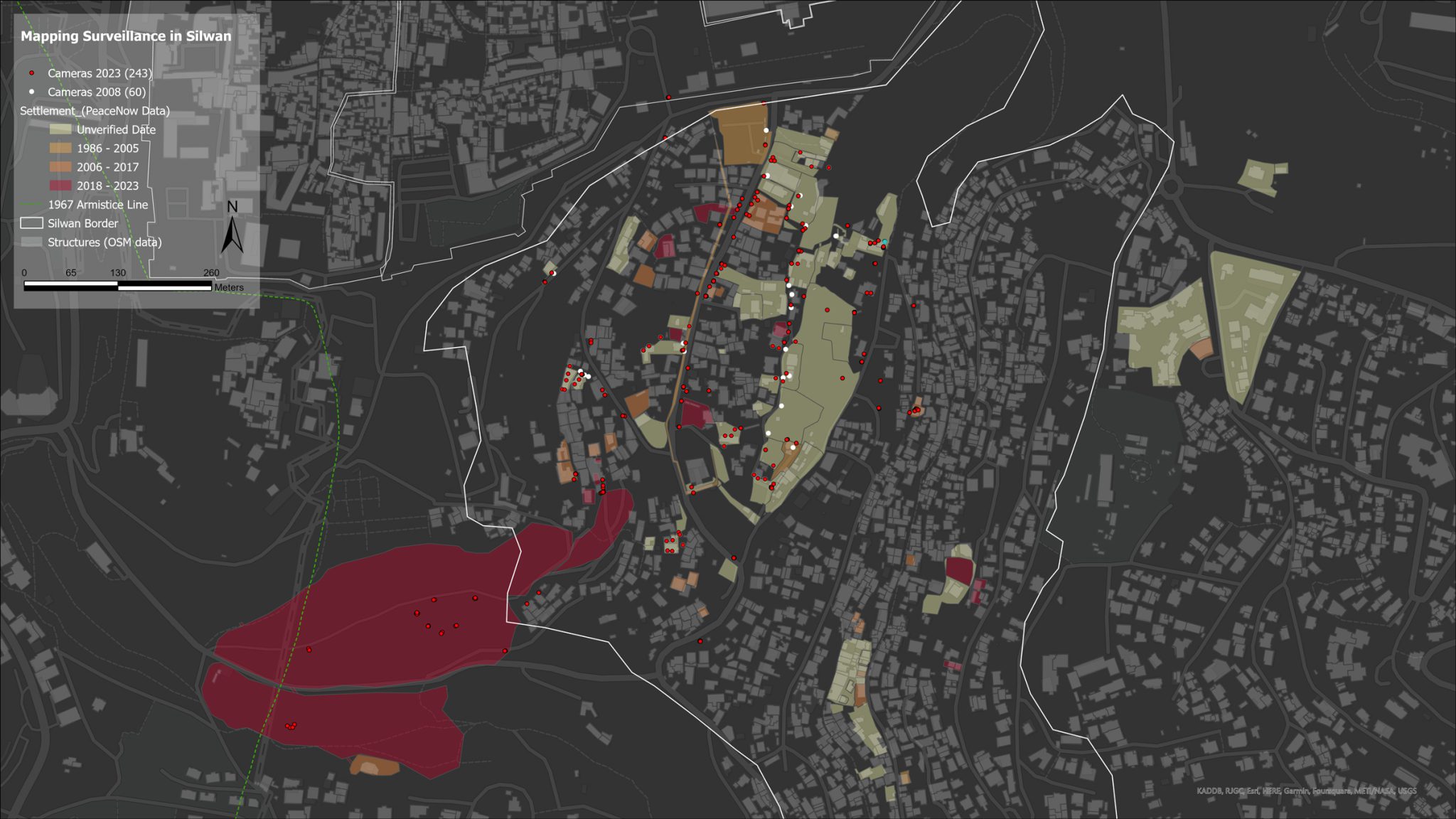

▴ Surveillance mapped in the Silwan neighbourhood of Wadi Hilwe, courtesy of the Post-Visual Security project, Tampere University

Settler surveillance developments

In Silwan, a Palestinian neighbourhood in occupied East Jerusalem located immediately to the South of the Old City, Palestinian communities are slowly being hollowed out by the presence of military, intelligence and the encroachment of Israeli settlers and settler organizations.

In 2009, the Israeli settler organization Elad, in cooperation with Israel’s Ministry of Housing, the Jewish National Fund/KKL, and the Jerusalem Municipality, initiated an effort to expand excavation efforts of the City of David archaeological site. The plans came at the expense of some 70% of the land of Silwan, including entire residential areas, which according to Al-Haq, were labelled as “open areas”. Al-Haq reported that the plans “called for the destruction of 88 Palestinian houses, inhabited by more than 1,500 Palestinians”.

In the same year, the Israeli Supreme Court rejected a petition by Palestinian residents to halt the City of David tunnelling project denying that significant damage would be caused to residential homes. The Court argued that there was insufficient proof of the “correlation between the tunnelling… and damage to Palestinian property”, and that any existing damage was “acceptable in light of the significance of the archaeological discoveries to Israel’s cultural heritage”. To add insult to injury, in addition to the violence and evictions, due to the damage to their homes, settler violence, and takeover of Palestinian properties, residents of Silwan informed Amnesty International that an increasing number of surveillance devices had been placed around Silwan by Israeli authorities, private security companies and by Israeli settlers. The latter were reported to have built homes on top of now-damaged Palestinians residences, from which the occupants had been driven out.

Towering surveillance poles dominate the centre of Silwan, while Palestinian homes form the immediate inner circle, rendering them hyper-visible. The outer ring consists of former Palestinian homes, now illegally occupied by Israeli settlers, identifiable by a mixture of barbed wire, Israeli flags and extensive surveillance devices, including smart cameras and ambient sound detection devices mounted on fencing, looking down at the inner Palestinian circle. In this way, and as settlement activity has increased, Palestinians in Silwan are increasingly watched from every angle, now living under the conditions of what might be best described as a double panopticon; from the centre looking out, and from the margins looking in.

The combination of settlement activity and the increase in surveillance equipment erected by Israeli settlers and security forces are part of an intentional strategy to create a hostile environment to force Palestinians to leave areas of strategic importance in occupied East Jerusalem, such as Silwan, in order to establish and consolidate domination and control.

Sara, who was born and continues to live in Ein al-Luza neighbourhood in Silwan, told Amnesty International about the changing landscape in Silwan:

“[T]he [Israeli] occupation forces set [surveillance] cameras all the way down the street. For example, cameras used to be mounted to the pole at the junction where you got off the bus, but [Palestinian] young men burned them down because they used to detect them during the clashes [with the Israeli occupation forces]”.

Sara emphasized how the invasive nature of the camera surveillance, which she describes as having increased since the crackdowns on the Sheikh Jarrah protests, was making it difficult to go about daily life even inside their own homes. She explained that the camera pole in Bir Ayub, near Ein al-Luza, which activists had attempted to dismantle and burn down on 28 July 2021, is the “root cause of all the confrontations”, noting that there had been a recent expansion of surveillance cameras, including surveillance towers in particular.